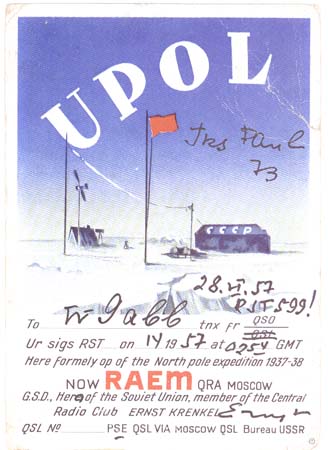

RAEM 1957 Arctic

Operator: Ernst Krenkel

This is the back of the 1957 card.

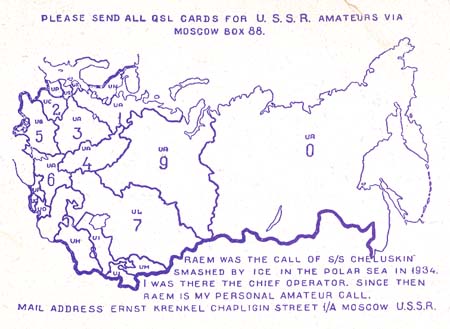

This is the back of the RAEM Ernst Krenkel card from 1964, 65, and 66.

Alex Rekach UA3DQ, Ernst Krenkel RAEM

The following is info from G4AYO:

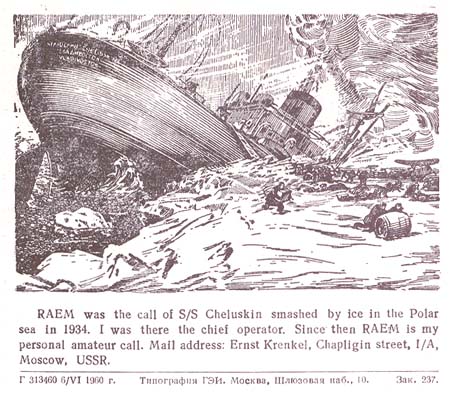

As I am sure you are aware RAEM was the callsign of the Chelyuskin which sank in the Arctic on February 13 1934. RAEM later became Ernst Krenkel's own amateur band callsign. When I heard Krenkel in 1968 he was signing RAEM/mm - on board the Professor Zubov on its way to Russia's Antarctic base.

In 1937 Krenkel was the radio

operator of the first North Pole station -

UPOL. The attached TEXT file is an account by Krenkel of his

radio activities

on the drifting ice of UPOL. You will see that Krenkel only had

QSOs with

just over 60 stations!

The QSL shown on your site (and several others) is that of RAEM (but of course also featuring UPOL which Krenkel was also famous for). Krenkel had a separate QSL for UPOL which is obviously extremely rare in view of that fact that he only made 60 QSOs! I have never seen this QSL on the internet.

Radio station "UPOL"

Our small three-valve receiver was designed for telegraphic work.

Nevertheless we understood broadcasting stations perfectly on it.

The loud-speaker rarely worked, the output was insufficient. Our

tent was therefore equipped with radio. Each of us had his own

pair of earphones. One could at will get into one's sleeping bag

with headphones, cover up one's head and listen in the warm to

the latest news from the Big Land.

In the light of summer time, the audibility of even such powerful

broadcasting stations, as Moscow, was weak. We only now and then

heard the Comintern (Communist International). Then, at the end

of August, audibility began to improve. With the approaching

polar darkness we had excellent and positive reception of Moscow

at any time.

It could be said with confidence that for these nine months we

were the most conscientious radio listeners of the Soviet Union.

In the middle of twelfth night, even with three minutes to go,

the receiver was still switched on, tuned in, and we four, with

bated breath, sat and waited, for our news from Moscow.

We were very well informed about all events at home and abroad.

With the collective of radio workers, especially with managers of

Moscow broadcasting centre, we established very warm friendly

relations. We sent them all sorts of questions, secured special

concerts, and asked to be given the chance to talk with our wives

and children in front of a microphone in Moscow. All these

requests they carried out promptly and thoroughly.

Besides Moscow, we had the opportunity to listen to most European

stations. High-powered stations could be received regularly each

day. During particularly favourable conditions the airwaves

literally swarmed with broadcasting stations. Even at the Pole

the difficulty was to tune in and separate these many stations.

It was interesting to observe the "pranks" of the air.

One day a telephone working quite low-powered stations of the

Rostov State farm was heard perfectly. Some evenings stations

such as Vladivostok and Budapest prevented me working Rudolf

Island. Sometimes at 4-5 o'clock in the morning Moscow time a

whole number of American stations was heard, but audibility was

fairly weak.

For the facilitation of astronomical observations we used a

microphone. Fedorov, outside the tent with his theodolite,

dictated his readings into the microphone, and one of us, sitting

with headphones in the tent, listened for Fedorov's report and

wrote down in the tent the reading and time according to the

chronometer.

One day I decided to make good use of this microphone and

inserted it directly into the antenna. Rudolf Island heard us. It

is true, badly, the modulation was quite weak, but everything was

heard. I did not consider it possible to delve into the sealed

transmitter. In our condition it would have been a crime to

experiment with the working of the equipment. However I was sorry

that the transmitter was not telegraph-telephone. It is a pity

that my optimism with regard to the conditions for spreading

radio waves in the Arctic did not spread as far as the mainland.

Rudolf Island worked us all the time on 800 metres, using a

transmitter at 30 watts. Although it was a telegraph-telephone

transmitter, it never occurred to either of us to try telephone

transmission to Rudolf Island. Only after my attempt with

unsuitable facilities did Rudolf Island set its telephone working

and we heard it extremely well. It was a new source of joy.

In autumn aircraft from Moscow delivered newspapers, letters and

even gramophone records to Rudolf Island - talking letters from

friends and relatives. Letters were transmitted to us by

telephone and gave us many joyful minutes.

A special job in my work was contacting radio amateurs on

short-waves. Leaving Moscow, I promised radio amateurs of the

Soviet Union to actively maintain communications with them. It

was not my fault that I was unable to fulfil the promise in a way

that I would have liked.

As on many other occasions I was severely limited by the wind and

the batteries. At the slightest opportunity I tried to work radio

amateurs. But this work always went on only "under

wind". Not only accumulators had to be fully charged, but

while working radio amateurs there had to be a fresh wind. I

worked until the first signs of an abating wind in order to

ensure time to restore, with the help of the windmill, the

electric power output used up. Only with observance of these

conditions could working radio amateurs be permitted.

Nevertheless, since there was only little free time, I

"crept" onto the air for meetings with amateur radio

short-wave enthusiasts. In August Moscow announced a competition

- for the first radio amateur who got in touch with the Pole.

The first of Soviet short-wave enthusiast who established

communications with me was the old "enthusiast of the

air", Leningrader Saltykov. Only Vedchinkin contacted me

from Moscow. I also had contacts with other Leningrad short-wave

enthusiasts, with Sverdlovsk and Krasnoyarsk. Before take-off to

the Pole I left the editorial staff of the magazine "Radio

Front" my personal short-wave receiver, which I asked be

passed to the short-wave enthusiast who established the first

two-way communications with me. The receiver was awarded to

Saltykov.

On the ice we did not have elevators and tramways which usually

create deafening interference to the receiver. We had ideal

conditions for radio communications. With the help of a small

three-valve receiver I managed to make contact with all the

world. A Norwegian from Alesund made the first foreign contact

with me. Then a circle of acquaintances extended all over the

air.

Contacts with radio amateurs usually went on at night time.

Doubling as the night watchman of our expedition, I strolled

around the tent and the Globe, as my comrades peacefully slept in

their sleeping bags.

In a special notebook I precisely recorded the details of

communications with those stations with whom I had a

"QSO" - two-way communications, I noted the audibility

of amateur stations. On separate occasions I managed to get in

touch with most of the European States.

Norway, Sweden, England, Iceland, France, Czechoslovakia, Belgium

and Holland appeared in my log.

The USA, as the country having the greatest number of radio

amateur transmitters, stood in first place for the number of

contacts with the Pole. The American press was interested in the

work of our station. My UPOL callsign had only to appear on the

amateur bands and amateurs literally pounced on me with several

stations from various parts of the world and different continents

simultaneously calling me.

On one occasion successful communication was established, without

interruption, with eleven Americans in succession. They passed me

from hand to hand. A few friendly words and the person I was

speaking to passed me on. Conversations usually dragged on and

lasted longer than normal conversations between radio amateurs.

After the establishment of communications I was compelled first

and foremost to receive enthusiastic outpourings, offers of help

in the passing of radio messages, requests for regular

communications.

Friends showed up on the Hawaiian islands. I worked one of them

several times and he turned into a supporter of our expedition,

he was worried - would the ice melt, aren't you afraid?... He was

well-informed about our drifting expedition. He reported to us

the contents of our reports, only the day before they had been

printed in central Moscow newspapers. By his reports we saw how

quickly the foreign printing of our radio messages, sent to

Pravda and Izvestiya could be reprinted.

I successfully worked Alaska and Canada. The record for distance

was communications with stations in South Australia and New

Zealand. These stations were almost our antipodes.

Almost all communication, with rare exceptions, was made on 20

metres. Doubtless, this was a fine achievement for a 20-watt

transmitter

During the expedition two-way communication was maintained with

the following amateur stations:

>From 27 May to 31 July inclusive. (from 89ø to 88ø North

latitude)

LA1M (Norway) F8IS W2CYS (USA New York) PA0AS GI5AJ G6KP G5RI

TF3C U1AD (Leningrad) U1AP (USSR, Leningrad) W1EWD (USA Rhode

Island) OK1PK ON4BW D3FZI (Germany) U3CY (Moscow) PA0FF UK1CR

(USSR, Rudolf Island) D3GKR F8AI PA0GN K6SO (Hawaii) VK5WK VK2DG

>From 1 August to 31 October inclusive (from 88ø to 84ø

North latitude)

SM5UW W7LQS VE5LD G5MY W8PMB W1AEF W9PNE GM2JF W2KAP

>From 1 November to 4 December inclusive (from 84ø to 82ø

North latitude)

W2SB W2FSN W8EME K7RT G5JX F8GQ W9THH W9ALV W9VDQ W8CMH W8HRD

W8NOT W9AJA W9PLX W8BGX W8LSK W8DFH U1CO (Leningrad) ZL4BR U9ML

(Sverdlovsk) W1HUD GM2JF W2BHW W2GTZ PA0DA SM5WM SM5QU U1AD

(Leningrad) U1BC (Leningrad)

Read the Ernst Krenkel RAEM Story by RW3GA!

QSL from the estate of W9ABB /

W9HK

Ernst Krenkel story on this page by G4AYO

Ernst Krenkel Story by RW3GA, courtesy of G3ZPF

Photo from Don Chesser W4KVX DX Magazine #106, August 17, 1960

Photo sent to DX Magazine by W4GD