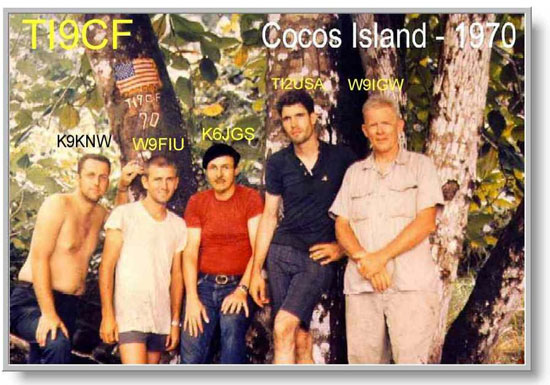

TI9CF 1970 Cocos Island

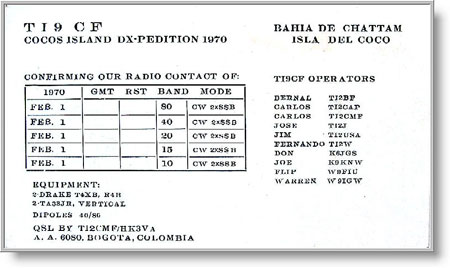

The operators were Bernal Fonseca TI2BF (Brother of Carlos Fonseca TI2CF), Carlos TI2CAP, Carlos Manuel Fonseca TI2CMF (Carlos later changed his callsign to TI2CF, Jose TI2J (As I recall Jose went to Serrana Bank in 1971, Jim TI2USA (Jim was a Marine guard at the U.S. Embassy in 1970, Fernando TI2W, Don Blankenship K6JGS (today W4PUL), Joe Goggin K9KNW, Roger "Flip" Ries W9FIU, Wayne Warden W9IGW, now W9GW.

THIS IS A CLASSIC STORY OF

HOW NOT TO CONDUCT A DXPEDITION

The 1970 DXpedition group to Cocos Island almost cost the lives of all five Americans and about seven Costa Ricans. For the first time the story is told below.

The amateur radio group which eventually landed on Cocos operated only about 100 feet in from the shoreline at Chatham Bay. In 1970 the jungle growth was so thick down to the shoreline that it appeared impenetrable. Today it is completely cleared and there are open paths with wooden benches placed there by the Costa Rican Parks Authority.

When the 1970 DXpedition group landed on Cocos, they were utterly and completely exhausted following a dangerous storm ridden voyage from Puntarenas, Costa Rica. The passage in open seas during a terrible Pacific Ocean storm had completely exhausted the strength of the landing party. This fierce ocean storm almost sank their boat en route to Cocos the day earlier. This caused dangerous flooding of their chartered fishing vessel. Due to a faulty bilge pump, the tuna boat they used for the voyage actually began to sink in mid-ocean between Costa Rica and Cocos Island. This water pump became totally inoperative at a critical moment as the ship was taking on lots of water. It began to sink by mid-day following a storm the night before. After Roger Ries (W9FIU) made emergency repairs to the bilge pump the morning following the great storm, the boat then lumbered on to Cocos Island.

A second storm struck Cocos Island while the crew was landing and off-loading their equipment and before any food could be off-loaded to the island. The only dinghy bringing supplies and personnel to the island was demolished by the raging storm leaving the amateurs stranded ashore for four days with little or no food. The bottom of the dinghy was completely smashed after it was thrown upon the rocks on the small beach at Chatham Bay. With this as a backdrop you may understand why the amateur radio group was unable to consider any other options other than to try to operate close to the beach.

Due to the storm and the heavy cloud cover, the navigator was unable to get good star shots for his sextant readings. Plotting our course was done almost entirely with dead reckoning. Unfortunately, our course was very uncertain at best. So it is interesting and quite amazing that the island was located by using the pirate's method of dead reckoning. They also watched for frigate and other sea birds at daybreak as they flew outward from the island in radial flight to forage for food. The ship's captain then followed the reverse flight of the birds to find Cocos island. A very inexact science, but it worked for the old Spanish pirates and it worked for us as well. This was a DXpedition doomed to failure almost from the onset.

If there is something to be learned from this DXpedition fiasco in 1970, it is to only trust yourself and those who you have observed and tested. Simply put, you must only rely on the organizational and operational talents of people you know and absolutely trust. Also be assured that you have adequate funding for your expedition. In this particular case, the Americans along for this DXpedition were almost entirely at the mercy of their local hosts. One could say that the Americans were at fault for ever letting themselves be drawn into a situation of total trust of people they didn't even know and people who were primarily concerned with self interests. This reliance on others to do the planning and safeguard their lives while in a foreign country almost cost the Americans their lives when the boat almost sank. First among the most egregious abuses of confidence was when the Americans accepted a rickety old tuna boat to take them to Cocos Island from Puntarenas, Costa Rica. They also relied upon their hosts to provision the ship with supplies adequate for the four-day round trip voyage and subsequent stay on the island. DXpeditions require a tremendous effort to plan and execute. You don't simply travel to a remote location or foreign country and expect everything will neatly fall into place once you arrive. It simply won't. Murphy's law always prevails. Difficult or dangerous expeditions require extraordinary planning to assure they have a fair chance of success.

Because proper planning had not been done before the trip, the food supply for the expedition was woefully lacking. A quick dash by our local hosts to a corner grocery store in Puntarenas, Costa Rica, just before the ship sailed, represented what typified this unusual organizational plan. There were no shopping lists to buy adequate and appropriate provisions for the group. About three or four small cardboard boxes of tinned foods, such as sardines and mackerel, salt crackers, beans, rice and ketchup were purchased just hours before the voyage. This small amount of food was entirely inadequate to sustain the group over the duration of the round trip to Cocos Island. No questions had been asked of the Americans concerning what they would like to eat nor had any thought been given to how the food would be prepared. I recall mostly eating boiled rice with a tomato ketchup topping or sauce, with perhaps a spoon sized portion of sardine for most of the meals during the trip to and from the island. There was obvious discomfort because of the inadequate food portions and the lousy taste of the food itself. The mood among the Americans was one of anger for having been deceived by our hosts. However, we tried to be good guests and make the most of it because, after all, we were going to be operating from Cocos Island, a DX location relatively rare in 1970. Much of our pain and discomfort was simply tolerated and any manifestation of anger deferred until after the expedition was over. That is what mature grown men do in times of adversity. However, each of them promised that it would never happen to them again. Some of the group, such as K9KNW (Joe Goggin) and W9IGW (Wayne Warden) went on to complete several other DXpeditions including Juan Fernandez (CE0), San Felix CE0), Bajo Nuevo (HK0) and San Andres (HK0).

Once on the island, the situation was very bleak during the first 12 hours. Tremendous storms brought lightning and thunder claps so loud, it was absolutely deafening through the thin walls of the tent. Shortly after our arrival, we managed to set up one tent before the worst of the storm hit. In spite of our careful efforts, the downfall of torrential rain filled the interior of an otherwise rainproof tent. Water on the floor of the tent was about 1 inch deep and we simply were unable to evacuate it. We therefore later fell asleep in the crowded tent with about an inch of water on the floor. It was cold and miserable and just about the very worst night anyone ever spend on one of these "so-called" DXpeditions. During the first night, the tumultuous winds from the storm and the ferocious ocean currents washed one of our generators out into water. The powerful wave action on the beach crashed the dinghy up and down upon the rocks such that by morning there was absolutely no bottom, only one big hole where a bottom used to be. The radio equipment had been wrapped in plastic but both generators had water damage and required extensive cleaning the following day. We were off to the very worst possible start one could imagine. We also had lost our small boat, our life line to the mother ship which waited for us out in the harbor. There was no way to transit between the tuna boat and the island. We were, for all intents and purposes "stranded on Cocos Island" and would remain so for the next four days. We had no contact with the other Costa Rican group that remained aboard the tuna boat. To them, it probably didn't matter very much because their gratuitous trip was to fish near Cocos Island. And.....the worst part of it was we all were hungry.....terribly hungry! However, for the Americans, the sole purpose of going to Cocos Island was only to operate their amateur radio equipment. So the fisherman aboard the tuna boat simply disappeared for a lengthy period of time and left the Americans and two Costa Rican amateurs on the island to fend for themselves.

During the following few days the amateurs were on the island, they managed to exist by eating the few precious treats that Flip (W9FIU) had stowed away as his personal supplies because of his finicky eating habits. Then when the weakness from famine began to seriously affect the group, Jose (TI2J) took his .22 cal. rifle out into the jungle growth and was able to bag a small deer. With this venison meat and a little bit of rice that had been brought along to the island, the amateurs were able to cook a proper meal and regain their strength. I also recall that later someone also rigged a fishing line of some sort and caught a few fish. Without these emergency measures taken to acquire food, the amateur radio group would have been in very serious circumstances as their health deteriorated.

As it turned out, about four days after the amateurs arrived on the island, a Nicaraguan fishing boat approached Cocos Island. They quickly were summoned by the tuna boat that brought us to the island. They were then asked to aid in our rescue if they could provide a small dinghy that could be used to extricate us from the island. They were told that our dinghy was now inoperable due to a bad storm. The Nicaraguan fishing vessel accommodated us and even provided a man to row a small boat back and forth from the island to the chartered boat. Using the small boat, we eventually were able to depart the island with all of the equipment we brought with us. In spite of all the bad luck and very poor planning, the amateur radio group was still able to make about 4,000 contacts from Cocos using the callsign TI9CF.

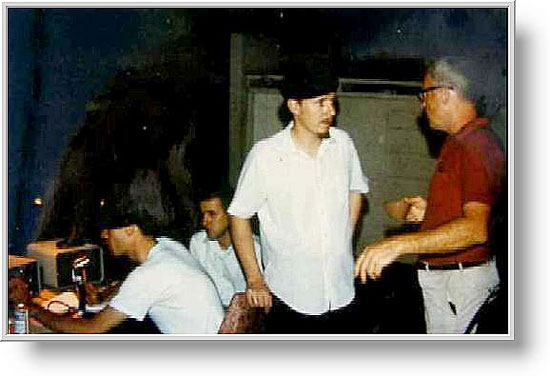

Don Blankenship K6JGS/W4PUL speaking with Wayne Warden W9IGW in San Jose, Costa Rica just before the launch of the expedition. In the background Jim TI2USA and Flip Ries W9FIU.

The tuna boat that took the expeditioners to Cocos Island.

From Left to right K6JGS "Don" and W9FIU "Flip" en route to Cocos Island aboard a tuna boat. Flip had just presented his Ph.D thesis prior to this trip. He worked for the U.S. Navy at the University of Urbana in Illinois and also worked part time for Joe Goggin in his mobile electronics business. He obviously was a very bright guy and also an excellent contest and DX operator.

Joe Goggin, K9KNW, Flip Ries W9FIU, Don Blankenship K6JGS/W4PUL, Jim TI2USA, Wayne Warden W9IGW. Jim was a U.S. Marine security guard in San Jose, Coast Rica. He was very tall as you can see in this photo. Not shown are the Costa Rica hams that include Bernal Fonseca TI2BF, Carlos Fonseca TI2CMF, Carlos TI2CAP, Jose TI2J, Fernando TI2W. Notice the carving in the tree on the left.