Legends and Lore of Cocos Island

by Peter Tyson

Jacques Cousteau deemed it "the most beautiful island in the world." Michael Crichton wrote "Jurassic Park" with it in mind. Robert Louis Stevenson may have based his classic "Treasure Island" on it.

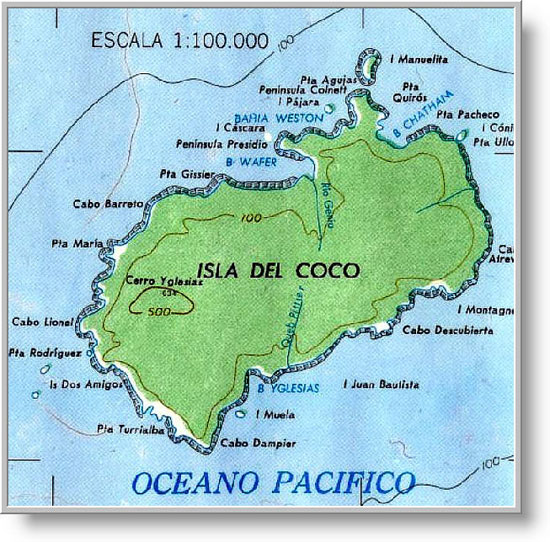

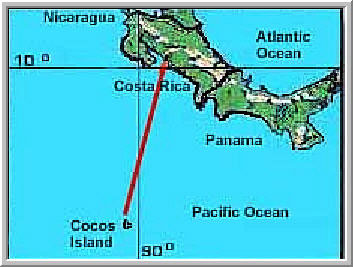

Cocos Island, 300 miles off the coast of Costa Rica, is legendary for its natural and man-made treasures. The largest uninhabited island in the world, this 10-square-mile tip of an ancient volcano is the only isle in the eastern Pacific that bears rainforest. From the precipitous cliffs towering over the craggy shoreline to the 2,079-foot summit of Mt. Iglesias, the island's highest peak, the luxuriant bed of jungle is rivaled only by scores of sparkling waterfalls that tumble out of the heights.

Yet it is for buried treasure that Cocos is perhaps most famous. Over the centuries before the Republic of Costa Rica assumed control of the island in 1869, pirates used Cocos as a buccaneer bank, secreting priceless artifacts and tons of gold bullion in its inaccessible hillsides. If the legends are to be believed, many of these pirates died from disease, battles, or execution before they could ever return to the island to claim their loot, and it remains there to this day, hidden in natural caves or long-forgotten trenches. One estimate puts the accumulated treasure, if it is indeed all still there, at over $1 billion.

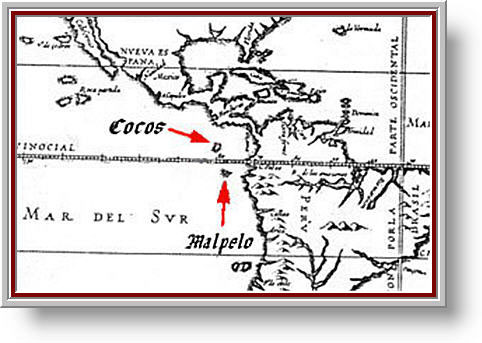

Cocos' story begins in 1526, when the Spanish pilot Johan Cabešas first discovered the island. Sixteen years later, it appeared for the first time on a French map of the Americas, labeled as Ile de Coques (literally "Nutshell Island" or simply "Shell Island"). The Spanish apparently misunderstood the French name and called it Isla del Cocos ("Island of the Coconuts"), which proved apt enough. "`Tis thick set with Coco-nut Trees, which flourish here very finely," wrote Lionel Wafer, a surgeon who penned one of the earliest descriptions of this island after a visit in the late 1600s. So abundant were coconuts that Wafer's companions made a bit too merry with the milk one afternoon, drinking 20 gallons at a sitting: "That sort of Liquor had so chill'd and benumb'd their Nerves, that they could neither go nor stand; nor could they return on board the Ship, without the Help of those who had not been Partakers in the Frolick . . . ."

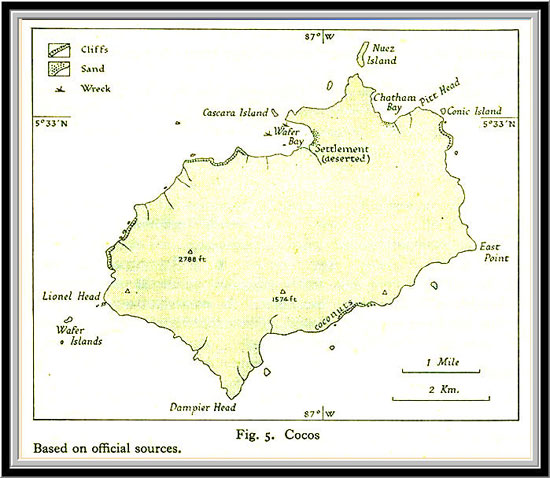

Over the next century, the island became a kind of oceanic truck-stop, where ships of all stripes could rest and take on freshwater, firewood -- and coconuts. Whalers stopped there regularly until the mid-19th century, when their industry in the region collapsed due to overfishing. Captains with missions ranging from exploration to administration of justice dropped anchor in Chatham or Wafer bays, the island's principal harbors. More than any, however, pirates made Cocos their home.

The Golden Age of treasure-burying on the island took place in just a few years on either side of 1820. It all began in 1818, when Captain Bennett Graham, a distinguished British naval officer put in charge of a coastal survey in the South Pacific aboard the H.M.S. Devonshire, threw up his mission for a life of piracy. He was eventually caught and executed along with his officers, the remainder of his crew being sent to a penal colony in Tasmania. Twenty years later, one of the crew, a woman named Mary Welch, was released from prison bearing a remarkable tale. She claimed to have witnessed the burial of Graham's fortune -- 350 tons of gold bullion stolen from Spanish galleons. (A recent estimate put the treasure's present-day value at $160 million). Moreover, she had a chart with compass bearings showing where the so-called "Devonshire Treasure" was buried. Graham had given it to her, she said, just before he was captured, thinking -- rightly as it turned out -- that it would be safer on her person than on his. Welch's story was believed, as much for her intimate knowledge of the island as for the chart, and an expedition was mounted to hunt for the treasure. Welch went along, of course, and as quite an old woman set foot once again on Cocos. In the decades since she'd been there, however, the lay of the land had changed so much at the hands of visiting sailors that many of her identifying marks, including a huge cedar tree near which she had once camped for six months, had disappeared, and the expedition recovered nothing.

A Spanish map from 1622 showing the location of Cocos and Malpelo Island.

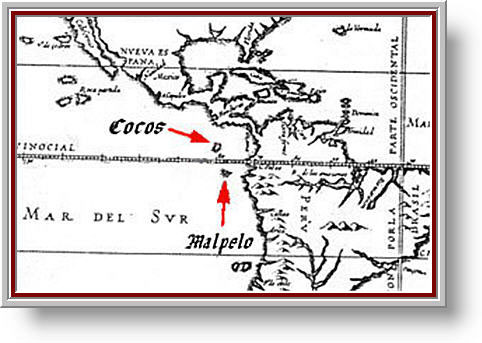

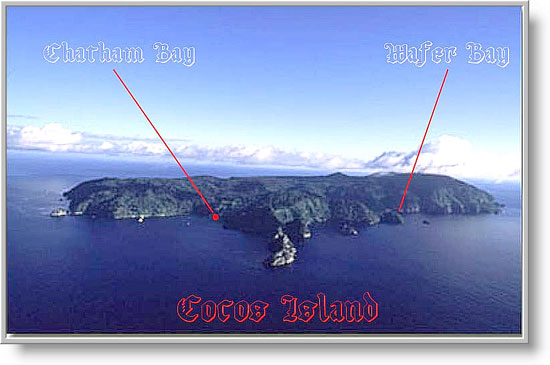

This is the northeast facing of Cocos Island. The red dot shows where the TI9CF expedition took place. You can see that propagation to the northwest at low elevation angles was hampered due to nearby hills.

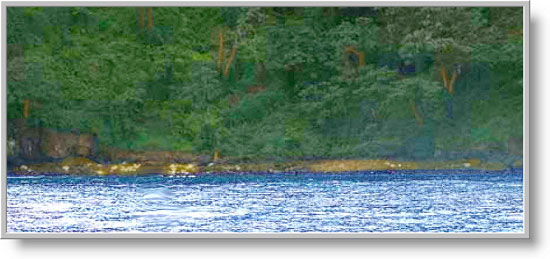

Here you see the stand-off distance for the charter boat that took us to Cocos Island. The row boat had to traverse this distance to the beach carrying equipment, supplies and personnel.

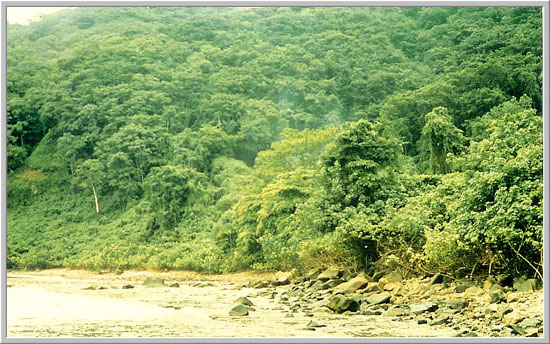

Closer Approach to the landing site at Cocos Island

There is very thick jungle growth right down to the water line. Cocos has plenty of flora. There are deer and we heard mention of wild boar on the island as well. Obviously there are lots of birds. Fishing is some of the best in the world due to the cold Humboldt current that flows past the Galapagos, Malpelo and Cocos. There is said to be fresh water streaming off the hills after tropical rainfall. The island once was use by pirates during the 1600's and 1700's. It's said there was about 100 million dollars worth of gold buried on the island. This was in 1970 when gold was selling for $36 dollars an ounce. Today that same amount of gold, if it's still buried there, would be worth $2.7 Billion dollars.

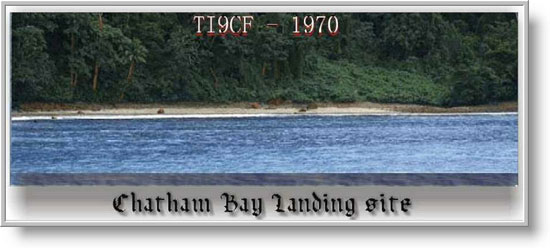

Captain Christian, an old German sea captain who took us to Cocos Island, had many interesting stories to tell us. He told a story about once taking some treasure hunters out to Cocos. They were very, very secretive and spent a lot of time whispering among themselves. While the treasure hunters were on the island, Capt. Christian discovered they left a copy of their treasure map behind on his ship. He studied it very carefully and could see that it showed evidence of five pillars or rocks at the beach. This is what the treasure seekers were looking for and had asked Captain Christian about. He told them he'd been to Cocos many times but never seen those five pillars they were talking about. The treasure seekers left after a few days of searching for the buried gold. A few years later Captain Christian was at Chatham Bay during a neap tide when the water level is at a minimum due to the position of the moon. He said he saw those five rocks he'd seen on the map but couldn't remember the relationship of the rocks to where the gold was shown to be buried on the treasure map. He got excited and began to dig on the island himself but soon realized that without metal detection equipment, he'd never find the buried gold. Even the government of Costa Rica has send expeditions looking for this hidden pirates gold. One man actually lived on the island several years looking for it. None has ever been found. Captain Christian was sure that the pirates, being a lazy bunch, would never have gone into the island very far to bury their gold. He was certain it must be at Chatham Bay somewhere near the beach.

This is a photo of Chatham Bay on Cocos Island. This site and Wafer Bay are the two most accessible landing sites on the island. The beach is very rocky and it's were an ocean storm broke apart our only row boat during our 1970 expedition. Very dense jungle growth goes all the way down to the beach area.

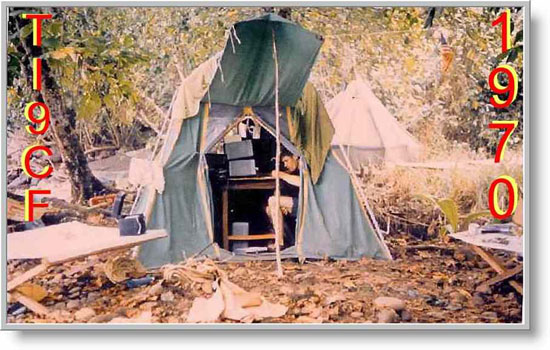

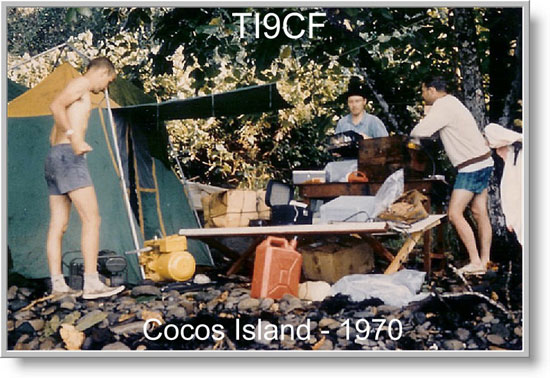

This was the ops site area just behind the beach area which is all rocks. The SSB and CW stations were about 100 feet to the left of where this photo was taken. You could use a machete all day and hardly cut out a large enough area for an ops site back then. This beach was completely flooded just hours after we landed. The tail end of the storm later hit Cocos Island and broke upon these rocks the only life boat the group had. The tail end of the same storm washed one of the generator plants into the sea, damaging it. The torrential rains caused some of the radio equipment to be damaged and one of the multiband vertical antennas was broken and carried out to sea. We could see the shark fins swimming out about 150 away from the beach. It is a breeding grounds for a number of different types of sharks. About 4,000 QSO's were made during a four day period.

Don K6JGS getting ready to operate.

In 1971 there was another DXpedition to Cocos Island. This time it was W4VPD Enos Schera and Don Riebhoff K7CBZ, who accompanied Carlos, TI2CF and Jose TI2J. Don Riebhoff later changed his callsign to K7ZZ. I helped get Don Riebhoff aboard this expedition. This one experience caused Don to be bitten by the bug for DXpeditions and he later went on to operate from Spratley Island, Saigon, Vietnam and Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

| Back to Page 1 |

QSL, Photos & Story courtesy of W4PUL